Vera2, Elections & Voting

The Supreme Court, Once Wary of Partisan Gerrymandering

Supreme Court’s Shift on Partisan Gerrymandering

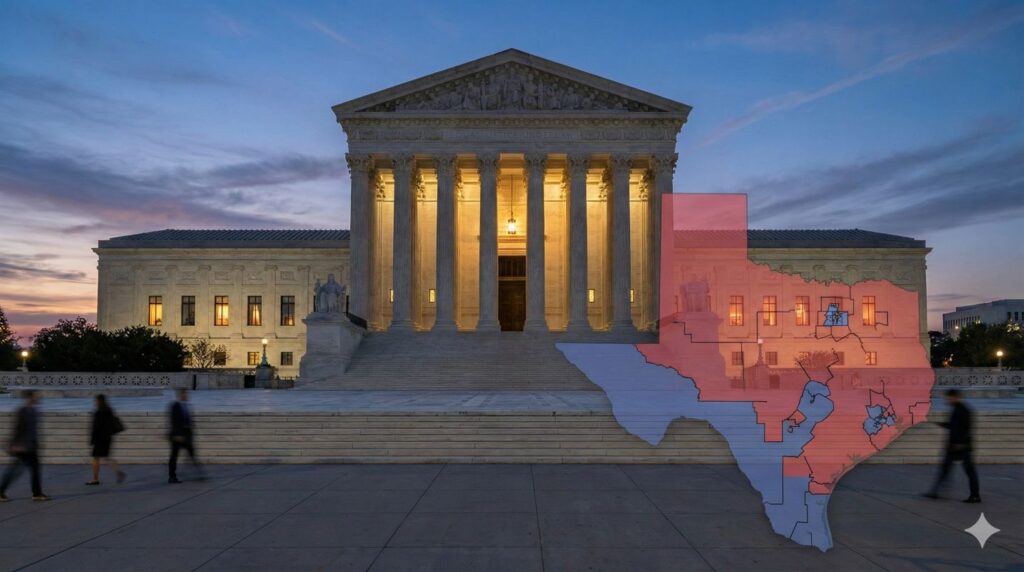

The Supreme Court’s shift on partisan gerrymandering is no longer a theoretical concern. In early December 2025, the Court’s conservative majority allowed Texas to use a new congressional map that a lower court had found likely unconstitutional because of its racial impact, while the state openly defended the plan as a partisan power play designed to lock in more Republican seats. That emergency order in Abbott v. League of United Latin American Citizens shows how the Supreme Court’s shift on partisan gerrymandering is working in practice, not just in doctrine.

The decision came on December 4, 2025, when the Court, by a 6–3 vote, granted Texas’s request to put a three-judge district court ruling on hold and let the state’s 2025 map go into effect for the 2026 midterm elections. The lower court had blocked the map after concluding that Texas lawmakers used race to achieve their partisan goals, but the majority treated the case as essentially a political gerrymander, not a racial one.

Background on Partisan Gerrymandering and the Court

To understand the Supreme Court’s shift on partisan gerrymandering, it helps to look back at how the Court has handled these disputes over time. Partisan gerrymandering is the practice of drawing election districts to benefit one political party and harm the other. Both parties have done it for decades, and the Supreme Court has long struggled with whether and how to police it.

In the 2019 case Rucho v. Common Cause, the Court’s then-5–4 conservative majority held that claims of partisan gerrymandering present “political questions” beyond the reach of federal courts. The Court acknowledged that extreme partisan maps can be “incompatible with democratic principles,” but said there was no workable constitutional standard to decide when political line-drawing goes too far.

That decision effectively shut the federal courthouse door to challenges that focus on partisan advantage alone. It did not say partisan gerrymandering is good or lawful in a moral sense; it said federal judges will not be the ones to fix it. Rucho pushed reform efforts toward state courts, state constitutions, and independent redistricting commissions, while leaving a gray zone where race and party are deeply intertwined.

The Supreme Court’s shift on partisan gerrymandering in the Texas case builds directly on Rucho. Now, when a state like Texas says that its goal is partisan gain and frames its redistricting choices as “political” rather than “racial,” that becomes a powerful shield against federal review.

The Texas Case: Abbott v. League of United Latin American Citizens

The Texas dispute that crystallized the Supreme Court’s shift on partisan gerrymandering grew out of a 2025 decision by the Republican-controlled legislature to redraw its congressional districts mid-decade. The new map was crafted after pressure from former President Donald Trump, who has pushed allies in red states to engineer more aggressive pro-Republican maps ahead of the 2026 midterms.

Under the new plan, Republicans are expected to control as many as 30 of Texas’s 38 U.S. House seats, up from 25 under the previous map. Analysis cited by Reuters and other outlets estimates that the design could flip up to five previously Democratic-held districts into the Republican column.

Civil-rights and Latino advocacy groups, including LULAC, challenged the map, arguing that Texas dismantled districts where voters of color had real influence and packed or cracked communities in ways that diluted their voting power. In November 2025, a divided three-judge district court sided with the challengers, finding that the legislature used the racial composition of districts to accomplish its partisan targets and that the map was likely an unconstitutional racial gerrymander.

The district court barred Texas from using the plan in 2026, but the state appealed and asked the Supreme Court for emergency relief. That is where the Supreme Court’s shift on partisan gerrymandering became decisive.

The Supreme Court’s Emergency Order

On December 4, the Court granted Texas’s request for a stay. In a brief order, a majority of justices allowed the map to be used while the appeal continues, stressing that federal courts should be cautious about changing election rules once a campaign cycle is underway.

Justice Samuel Alito wrote a concurrence, joined by at least two other conservatives, arguing that the district court had improperly treated a partisan map as a racial one. He emphasized that Texas had “avowedly partisan goals” and faulted the challengers for failing to present an alternative map that preserved those partisan objectives while using race less. That framing is central to the Supreme Court’s shift on partisan gerrymandering: if the motive can be described as party politics, the Court is far more deferential.

Justice Elena Kagan, writing in dissent for the Court’s three liberals, argued that the majority ignored the factual findings of the trial court, which had concluded that race “predominated” in the drawing of several key districts. She warned that the decision allows states to “cloak racial line-drawing in the garb of partisan aspiration” and erodes protections against racial discrimination in voting.

What the Texas Ruling Says About the Supreme Court’s Shift on Partisan Gerrymandering

The Court’s Texas order does not announce a new formal rule, but it illustrates how the Supreme Court’s shift on partisan gerrymandering works on the ground. First, by leaning on Rucho, the majority reaffirms that pure partisan gerrymandering claims are not justiciable in federal court. Second, by insisting that challengers prove race, not party, was the “predominant” motive, it makes racial gerrymandering claims much harder to win when party and race overlap.

Texas is a clear example. The state is only about 40 percent non-Hispanic white, yet white voters control more than 70 percent of its congressional seats, a disparity that civil-rights groups say the new map worsens. The district court treated that disparity, combined with detailed evidence about how lines were drawn, as proof that race guided the design. The Supreme Court’s majority, by contrast, treated the same record as evidence of sharp-edged politics, not unconstitutional discrimination.

In that sense, the Supreme Court’s shift on partisan gerrymandering gives states a roadmap. If legislators and their lawyers emphasize partisan goals and avoid explicit racial labels, they can pursue extremely aggressive maps with a lower risk of federal intervention, even when those maps disproportionately burden voters of color.

National Implications for Redistricting

The fallout from the Texas decision has been immediate. Reporting from the Associated Press, Reuters, and other outlets shows that Republican lawmakers in Missouri and North Carolina have already begun pushing new, more favorable congressional maps, explicitly citing what Texas achieved.

At the same time, Democratic officials in California have advanced their own redistricting changes that appear aimed at offsetting Texas by squeezing several Republican-leaning districts. Commentators at Democracy Docket and other election-law sites argue that the Court’s handling of Abbott v. LULAC signals open season for both parties to redraw lines mid-decade when it suits them politically.

Because the Supreme Court’s shift on partisan gerrymandering removes most federal guardrails, the main checks will now come from state constitutions, state supreme courts, and political backlash. In recent years, state-level decisions in places like North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Ohio have used state constitutional clauses on “free elections” or equal protection to strike down extreme maps that federal courts could not touch after Rucho.

How far this new wave goes will depend on politics within each state. Some legislatures may decide that maximal gerrymanders are worth the negative headlines if they secure a durable majority. Others may face pressure from voters to adopt independent redistricting commissions or more transparent line-drawing processes, precisely because the Supreme Court’s shift on partisan gerrymandering has limited federal oversight.

Responses from Elected Officials and Voting-Rights Advocates

Reactions to the Texas ruling mirror the broader divide over the Supreme Court’s shift on partisan gerrymandering. Texas Governor Greg Abbott called the decision a “victory for Texas voters and for our constitutional authority to draw districts,” emphasizing that the map had been approved by the elected legislature and signed into law.

Former President Trump and his allies framed the ruling as a key step in their strategy to retake and hold the U.S. House in 2026, praising the Court for allowing what they see as a legitimate use of political power by state lawmakers.

On the other side, civil-rights groups and voting-rights advocates have condemned the order. Democracy Docket described it as the Court “allowing Texas to use a racially gerrymandered map,” and The Guardian characterized the decision as a major blow for minority representation in a state where population growth has been driven largely by Latino and Black communities.

Legal scholars worry that the Supreme Court’s shift on partisan gerrymandering, combined with past decisions that weakened the Voting Rights Act, leaves communities of color with fewer tools to challenge maps that minimize their voting strength. They also note that emergency orders like the one in Abbott v. LULAC are increasingly used to make consequential election-law decisions without full briefing or oral argument, further raising the stakes of these “shadow docket” rulings.

Bottom Line

The Texas redistricting fight shows that the Supreme Court’s shift on partisan gerrymandering is now shaping real maps, real seats, and real elections. By allowing a map that adds up to five Republican-leaning districts to stand for 2026, even after a trial court found it likely racially discriminatory, the Court has signaled that it will give states wide latitude so long as they present their aims as political rather than racial.

For voters in Texas and beyond, the immediate consequence is a set of districts that are less competitive and more tilted toward one party. For the country, the broader consequence of the Supreme Court’s shift on partisan gerrymandering is a redistricting arms race that will likely intensify through 2026 and beyond, fought state by state, with far fewer federal guardrails than in the past.

Further Reading

Associated Press coverage of the Texas ruling and its impact on the national redistricting battle:

https://apnews.com/article/02b07b477b153f23ed5c387f2f9ae0c4

Reuters explainer on how the Court revived the pro-Republican Texas map and what it means for 2026:

https://www.reuters.com/world/us-supreme-court-revives-pro-republican-texas-voting-map-2025-12-04/

SCOTUSblog case page and analysis of Abbott v. League of United Latin American Citizens:

https://www.scotusblog.com/cases/case-files/abbott-v-league-of-united-latin-american-citizens/

Full Supreme Court order and opinions in Abbott v. LULAC (PDF):

https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/25pdf/25a608_7khn.pdf

Texas Tribune reporting on how the ruling reshapes Texas’s congressional map and strengthens Republican control:

https://www.texastribune.org/2025/12/04/texas-redistricting-map-us-supreme-court-2026-midterms/

Background on Rucho v. Common Cause and the Court’s decision to treat partisan gerrymandering claims as non-justiciable:

https://www.oyez.org/cases/2018/18-422

Democracy Docket’s analysis of the Texas ruling and what it may mean for other state maps:

https://www.democracydocket.com/news-alerts/scotus-allows-texas-to-use-racially-gerrymandered-map-in-2026-midterm-elections/

Connect with the Author

Curious about the inspiration behind The Unmaking of America or want to follow the latest news and insights from J.T. Mercer? Dive deeper and stay connected through the links below—then explore Vera2 for sharp, timely reporting.

About the Author

Discover more about J.T. Mercer’s background, writing journey, and the real-world events that inspired The Unmaking of America. Learn what drives the storytelling and how this trilogy came to life.

[Learn more about J.T. Mercer]

NRP Dispatch Blog

Stay informed with the NRP Dispatch blog, where you’ll find author updates, behind-the-scenes commentary, and thought-provoking articles on current events, democracy, and the writing process.

[Read the NRP Dispatch]

Vera2 — News & Analysis

Looking for the latest reporting, explainers, and investigative pieces? Visit Vera2, North River Publications’ news and analysis hub. Vera2 covers politics, civil society, global affairs, courts, technology, and more—curated with context and built for readers who want clarity over noise.

[Explore Vera2]

Whether you’re interested in the creative process, want to engage with fellow readers, or simply want the latest updates, these resources are the best way to stay in touch with the world of The Unmaking of America—and with the broader news ecosystem at Vera2.

Free Chapter

Begin reading The Unmaking of America today and experience a story that asks: What remains when the rules are gone, and who will stand up when it matters most? Join the Fall of America mailing list below to receive the first chapter of The Unmaking of America for free and stay connected for updates, bonus material, and author news.